Information to help others become better readers, writers, designers, and illustrators

Tuesday, December 7, 2021

Review: Louie Finds A Friend by Vivian Zabel

Sunday, December 5, 2021

Learn to Write for Children - 4 Basic Tools

By Karen Cioffi

We all know how difficult it is to break into the business of writing for children. Whether you write fiction or nonfiction, it is a tough business and can be overwhelming for those just starting out. While all writing must adhere to certain guidelines, writing for children has additional principles unique to its genre.

To start, the words used in children’s writing must be age appropriate. This may sound easy to do, but it can be a difficult task. There are also certain techniques and tricks used specifically in writing for children, such as the Core of Three, sentence structure, and the timeframe in which the story should occur when writing for young children. In addition, it’s essential to make sure your conflicts, storyline, and point of view are appropriate for the age group you’re writing for.

Along with this, there are general techniques for writing, such as adding sensory details, showing instead of telling, and creating an engaging story that hooks the reader right away, along with writing great dialogue and using correct punctuation.

This is just the beginning though, there is also the business of editing your work, writing a winning query, and following submission guidelines; the list goes on and on.

But, don’t get discouraged, there is help.

Here are four basic tools to get you started and guide you down the children’s writing path:

1. Children’s Writer’s WORD BOOK by Alijandra Mogilner is a great resource that provides word lists grouped by grades along with a thesaurus of listed words. This allows you to check a word in question to make sure it is appropriate for the age group you’re writing for. It also provides reading levels for synonyms. It’s a very useful tool and one that I use over and over.

2. Read and learn about how to write for children. There are plenty of books and courses you can find online that will help you become a 'good' children's writer. One in particular is with an excellent reputation is The Institute of Children's Literature.

3. The Frugal Editor by award winning author and editor, Carolyn Howard-Johnson, is a useful book for any writing genre, including children’s. It is great resource that guides you through basic editing, to getting the most out of your Word program’s features, to providing samples of queries. The author provides great tips and advice that will have you saying, “Ah, so that’s how it’s done.”

4. How to Write a Children's Fiction Book by award-winning author and successful children's ghostwriter Karen Cioffi.

Yes, it's my book, but it really is jammed packed with tips, advice, examples, and much more on writing for children. It also includes DIY assignments and touches on submitting your manuscript and book marketing.

I’ve invested in a number of books, courses and programs in writing and marketing, and know value when I see it. The products above have a great deal of value for you as a children's writer, and they are definitely worth the cost.

Remember though, the most important aspect of creating a writing career is to actually begin. You can’t succeed if you don’t try. It takes that first step to start your journey, and that first step seems to be a huge stumbling block for many.

Don’t let procrastination or fear stop you from moving forward - start today!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karen Cioffi is an award-winning children’s author, a successful children’s ghostwriter with 300+ satisfied clients worldwide, and an author online platform instructor with WOW! Women on Writing. For children’s writing tips, or if you need help with your children’s story, visit: https://karencioffiwritingforchildren.com

You can check out Karen’s books at: https://karencioffiwritingforchildren.com/karens-books/

Monday, November 29, 2021

Grammar in Writing IS Important

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard or read, “Why should I care about using correct grammar in my writing? That’s why they have editors.” Wrong! Most publishers don’t edit much writing that comes their way, IF they even accept any error-filled manuscript. Paying for an experienced, dependable literary editor is expensive, and the editors themselves will do only so much.

Some writers fight the idea that grammar (including sentence structure, punctuation, subject/verb agreement, pronoun usage, spelling, etc.) impacts the worthiness of writing, which is like saying failing to lay a solid foundation does not impact the stability of a building. Good grammar is extremely important. Good grammar shows the writer's professionalism and attention to detail. The writer will also be able to give an explanation that is understood.

Grammatical errors can cause confusion, and, in the worst-case scenarios, they can completely change the meaning of a sentence. A writer not knowing how to use good grammar will make writing difficult to read. Poor grammar (including all subtexts) breaks the flow of reading, annoys the reader, and reflects badly on the writer. No-one wants to be jarred from a really interesting read by poor punctuation or glaring grammatical errors.

Writer Melissa Donovan states:

Too many times I’ve heard aspiring writers shrug off good grammar,

saying they’d rather focus on plot or character, they’d prefer to use a

natural, unlearned approach to keep the writing raw, or they will simply

hire an editor to do the dirty work.

I have a hard time buying into those lines of reasoning. Refusing to bother

with grammar is just plain lazy, especially for writers who yearn to be more

than hobbyists.

Why should writers embrace grammar rather than make excuses for ignoring it?

I am not able to cover a complete grammar course here, but I will give a few areas to give writers a beginning. Here are ten reasons why good grammar should be a

central pursuit in writing efforts:

1. Readability

If your work is peppered with grammatical mistakes and typos,

your readers are going to have a hard time trudging through it. Nothing

is more distracting than being yanked out of a good story because a word

is misspelled or a punctuation mark is misplaced. You should always

respect your readers enough to deliver a product that is enjoyable and

easy to use.

2. Communication

You can’t engage with others in your profession if you don’t speak the

language of your industry. Good luck talking shop with writers and

editors if you don’t know the parts of speech, the names of punctuation

marks, and all the other components of language and writing that are

related to good grammar. And, good luck communicating with most readers

if you don’t know how to correctly use grammar.

A current problem I find lately involves contractions between

subjects and verbs in the narrative (non-dialogue) parts of manuscripts.

We talk using contractions between subjects and verbs, so using them in

dialogue works. However, even if the manuscript is written in first

person, the narrative is not dialogue. Contractions between subjects and

verbs in the narrative portion can result in passive voice or in

confusion. For example, I’d could mean I would, I could, I should, I

had. The reader shouldn’t have to decide what the author meant. He’s

means he has or he is, passive voice, which we need to avoid to have

good writing, clear communication.

3. Getting Published

How will you get that short story, essay, or blog post published if you

don’t know the basics of grammar, spelling, and punctuation? Sure, some

managing editors will go over your work and clean it up for you, but

most reputable publishers have enough submissions that they can toss

grammatically weak work into the trash without thinking twice.

4. Working with an Editor

I love it when writers say they can just hire an editor. This goes back

to communication. If you can’t talk shop with other writers, you

certainly won’t be able to converse intelligently about your work and

its flaws with a professional editor. How will you respond to feedback

and revision suggestions or requests when you don’t know what the editor

is talking about? Remember, it’s your work. Ultimately, the final

version is your call, and you won’t be able to approve it if you’re

clueless about what’s wrong with it.

Also, you need to hire the right kind of editor. An English

teacher can possibly find grammar errors, if she actually understands

grammar (Note: not all English teachers teach grammar anymore). However,

not all English teachers can edit for other parts of a successful

manuscript.

5. Saving Money

Speaking of hiring an editor, you should know that editors will only go

so far when correcting a manuscript. Returning work to a writer that is

solid red with markups doesn’t make either the editor nor the author

feel good. Most freelance editors and proofreaders have a limit to how

much they will mark up any given text, so the more grammar mistakes

there are, the more surface work the editor will have to do. That means

she won’t be able to get into the nitty-gritty and make significant

changes that take your work from average to superior because the amount

of work needed to make the manuscript readable.

6. Invest in Yourself

Learning grammar is a way to invest in yourself. You don’t need anything

more than a couple of good writing resources and a willingness to take

the time necessary to hone your skills. In the beginning, it might be a

drag, but eventually, all those grammar rules will become second nature,

and you will have become a first-rate writer.

7. Respectability, Credibility, and Authority

As a first-rate writer who has mastered good grammar, you will gain

respect, credibility, and authority among your peers. People will take

you seriously and regard you as a person who is committed to the craft

of writing, not just some hack trying to string words together in a

haphazard manner.

8. Better Writing All Around

When you take the time to learn grammar, using correct grammar becomes

second nature. As you write, the words and punctuation marks come

naturally because you know what you’re doing; you’ve studied the rules

and put in plenty of practice. That means you can focus more of your

attention on other aspects of your work, like structure, context, and

imagery (to name a few). This leads to better writing all around.

9. Self-Awareness

Some people don’t have self-awareness. They charge through life

completely unaware of themselves or the people around them. But, most of

us possess some sense of self. What sense of self can you have as a

writer who doesn’t know proper grammar? That’s like being a carpenter

who doesn’t know what a hammer and nails are.

10. There’s Only One Reason to Abstain from Good Grammar

There is really only one reason to avoid learning grammar: the writer is just plain lazy. Anything else is a silly excuse.

No matter what trade, craft, or career one is pursuing,

everyone starts with learning the basics. Actors learn how to read

scripts. Scientists learn how to apply the scientific method.

Politicians learn how to… well, never mind what politicians do. We are

writers. We must learn how to write well, and writing well definitely

requires using good grammar.

William B. Bradshaw, and author and writing expert says:

Whenever I get on my soapbox about grammar, people often tell me I put too

much emphasis on the importance of grammar -- after all, they say, why does

it matter what kind of grammar people use; the important thing is whether or

not they understand what they are saying and writing to one another.

According to Barry Kelly in “Why Grammar Is Important in

Writing,” “Grammar does play a vital role in creative writing. Proper

grammar is necessary for credibility, readability, communication, and

clarity. Mastering grammar will allow you as a writer to make your work

clearer and more readable.”

Grammar is the foundation for communication. Let’s examine some grammatical mistakes:

She was deeply effected by the death of her beloved pet. Affect is a verb, not effect (noun)

“Its over their.” She gestured to the large mahogany table slowly decaying in the corner. It’s over there.

Mary didn’t know weather it was time to go or not. Whether

He bought milk when he should of bought bread. Have rather than the word of

Let’s eat Mary. and Let’s eat, Mary.

Can you see how the first example could end up with Mary being eaten for dinner?

Goats Cheese Salad – crispy lettuce, juicy tomatoes, cucumber, goats, cheese

Vegetarians are certainly going to be put

off this salad when they realize it contains not only

cheese, but goats!

My interests include cooking dogs, walking, reading and watching films.

Oh dear, those poor dogs. I wonder who

gets to eat the canine culinary delights created by this

person?

There is used in place of their or they're, or one of the others is used incorrectly.

It's and its are not interchangeable.

Your and you're are not the same.

Commas are not used where needed, or they are sprinkled like

rose petals everywhere possible. Run-on sentences create a feeling of

confusion in the minds of readers.

I don't want to read a book by someone who can't manage to

understand the difference between homonyms (words that sound alike but

have different meanings) and/or what version of a pronoun is used as the

object of a preposition.

For example, I often hear (hear not here), "That's important

to Mary and I." Really? He would say "That's important to I"? Actually,

that is what he did say. A compound object is the same form pronoun as a

singular object. And, I have heard and read that problem from so called

well-educated people. Anything between a speaker or writer and another

person means the object form MUST be used: between John and me; between

my husband and me; between you and him.

I, he, she, we, they are subjects; me, him, her, us, them are

object forms; my, his, her/hers, ours are possessive forms. Object

forms are not to be used as subjects. Example: Mary and him went to

town. (test – him went to town. Uh, no, he went to town.) Subject forms

are not possessives even if a writer adds an apostrophe and an s.

Example: John’s and I’s reports are due tomorrow. Uh, no, should be

John’s and my reports are due tomorrow. Subject forms are never used as

objects, as discussed above. Example: The packages are for John and I.

(test – packages are for I. No, packages are for me.)

1. Correct grammar is required (except in the case of dialogue in dialect).

2. Correct sentence and grammatical mechanics are needed. This point

means correct subject/verb agreement, correct sentence structure,

correct pronoun reference and usage, sentence variety, etc.

3. Correct spelling is a MUST. Correct spelling includes using correct

words in context. Words that sound the same but are spelled differently

are misspelled if the wrong word is used: For example, they're, their,

and there mean completely different things.

4. Correct punctuation is important to avoid confusion.

IF a person wants to be a REAL writer, he/she must know

grammar to be considered professional. Therefore, if you don’t have a

good grasp of grammar and all of its subtexts, learn. Find a good

easy-to-understand book of grammar and read it, refer to it, and use the

knowledge inside it. Find websites with grammar lessons and

information.

Grammar has much to do with good writing. Josh Price for

Writing Studio, May 1, 2021, states: “Grammar ensures everything you

write is clear; good grammar makes your writing sound professional,

which gives it authority; good grammar allows your writing to be more

persuasive and competitive; and you express yourself better with better

grammar.”

Tuesday, November 9, 2021

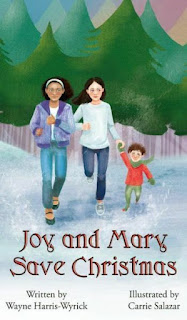

Review: Joy and Mary Save Christmas by Wayne Harris-Wyrick

Joy and her friend, Mary, are taken on a magical adventure to help Santa and the elves when stolen presents and electrical problems hit the North Pole in Joy and Mary Save Christmas by Wayne Harris-Wyrick.

Sunday, November 7, 2021

Writing Fiction vs. Writing Nonfiction

By Karen Cioffi

Writing fiction and writing nonfiction have some distinct similarities and differences.

But, before we get into that, let’s find out the definitions of fiction and nonfiction:

Fiction: According to Merriam-Webster.com, fiction is “something invented by the imagination or feigned, specifically an invented story; the action of feigning or of creating with the imagination.”

Nonfiction: Merriam-Webster’s definition of nonfiction is “literature or cinema that is not fictional.” According to Allwords.com, nonfiction is “written works intended to give facts, or true accounts of real things and events.”

Now on to the similarities and differences.

Writing Fiction and Writing Nonfiction Similarities:

1. You need to start with an idea.

2. You can write about almost anything.

3. You need ‘good’ writing skills (at least you should have good writing skills).

4. You need to have a beginning, middle, and end to the story.

5. You need to have an engaging, entertaining, informative, or interesting story.

6. You can work from an outline or you can seat-of-the-pants it.

7. You may need to do research.

8. You need to revise, proof, and edit your work.

Writing Fiction and Writing Nonfiction: Two Significant Differences

1. If you are writing nonfiction, you must stick to truths and facts, a nickel is a nickel, the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, two plus two equals four, and 10 times 10 equals 100. While there may be some grey areas, such as perspective, circumstances, or circumstantial evidence leading up to a fact based story, the fact is always the fact.

As an example: According to “The World’s Easiest Astronomy Book” (9/15/2009) by Hiroshi Nakagawa, “The speed of light is 300,000 km (186,000 miles) per second, meaning that light could circle the Earth seven and a half times in a single second. Even at this incredible speed it still takes light from the Sun eight minutes to reach the Earth. That means that when we see the Sun, what we actually see is the Sun from 8 minutes ago” (p. 13).

These are facts.

If you’re writing a nonfiction story about astronomy, these facts can’t change. Your story is limited to truths and facts. This is not to say the story can’t be amazingly interesting and engaging. The children’s middle-grade nonfiction book “The World’s Easiest Astronomy Book” can certainly spark a child’s imagination and interest in astronomy.

On the other hand, if you’re writing fiction, your imagination is your only limit. You don’t have to stay within the confines of what is known, what is truth. This offers a certain freedom.

If you want the sun to be ‘blood red,’ then it’s blood red. If you want to be able to travel to the moon in the blink of the eye, then it’s so. If you say a character can ‘walk through walls’ or is invisible, then he can and is. You can create new worlds, new beings . . . again, your imagination is your only limit.

2. In writing nonfiction you will most likely need to provide reference sources and add quotes to your story. This is to establish the reliability and credibility of your story.

In this case, you will need to reference the source of the quote.

If you notice above, in regard to the facts about the speed of light, I included the name of the book and the author along with the page number. These references substantiate the facts within your article. This makes your nonfiction story credible.

This is not the case with writing fiction.

With fiction, you will NOT need information references for credibility. Although, it’s important to realize that your fiction story will become its own truth and you will need to stay within the confines of the particular story and realm you create.

The reason for this: every story needs structure and intent; it needs to move forward to a satisfying ending. If you move off in too many directions, you’ll lose your intent and most probably your reader. To ensure the structure and your intent remains intact, you’ll need to stay within the confines of the story you create.

While the similarities between writing fiction and writing nonfiction seem to outweigh the differences, the differences are significant enough for most writers to prefer one genre over the other.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

You can check out Karen’s books at: https://karencioffiwritingforchildren.com/karens-books/

Tuesday, October 26, 2021

Review: A Baby Doll from Santy Claus by Vivian Zabel

Thursday, October 14, 2021

Edit! Revise! Edit! Revise!

For the past fifteen years I read and heard, “Don’t do any revising or editing until you have finished writing the whole story or book.”

What! That goes against common sense and everything I’ve learned in all the years I studied, wrote, taught, and read. The reasons I disagree are several, but a main one (and I have seen examples of this too many times) is if an author waits until after he finishes and then changes something toward the start, he often forgets a later part of the story affected by the change but not adjusted. A story develops from the beginning to end, and once written, any change at the beginning makes differences later in the piece, changes that are easy to miss. Thus cohesion and coherence become weak and faulty.

I know some “writers” who think any major editing should be done by an editor. Let me share something I found in the August issue of The Writer. According to Sam McCarver, the author of six John Darnell mystery novels,

In the time-intensive world of publishing, you may have only one

opportunity to intrigue an editor with your writing, your main

character and your story. And you must often do than within pages

– or the first few sentences – of your manuscript.

Editors are pressed for time and very perceptive in identifying good writing,

interesting characters and gripping stories, so they move fast through

your pages.

McCarver goes on to say that an author must write the best story or novel possible: edit it, polish it, enhance it. Then he should read and make final changes – all before ever allowing anyone else to read it. Yes, before allowing anyone else to read an manuscript, the author should have spent hours improving a rough draft.

Writing a story or novel is only half the job: Revising is the other half, a most important half, of writing. Ernest Hemingway, E.B. White, F. Scott Fitzgerald all admitted the need to revise and rewrite. Hemingway admitted he cut as he wrote, yet, he would take weeks to revise a book.

McCarver’s article “How to revise your FICTION” gives eight steps for editing a person’s work. I happen to agree with his points, especially the one which states that delaying all editing until the manuscript is finished is a mistake.

However, let’s examine this author’s ideas, as well as those expounded in many composition text books and believed by me:

1. Accept revising as the other half of writing. E.B. White stated that the best writing is rewriting.

2. Adopt good editing procedures. To produce a better first draft, one should begin revising with the first word written, making improvements as he goes. As a writer completes a day’s production, he should study what’s on the screen, if using a computer. If he sees a need for any changes, he should make them while they are fresh in his mind.. Then he should print what is finished.

According to Chang-rae Lee, winner of the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, he tries to polish as he goes because what leads him to the next sentence is the sentence before. "I find that it's hard to move on unless I've really understood what's happening, what comes before and where it's heading."

3. Review printed pages. Writers should print out the pages finished and set them aside to “cool.” Then they should read the printout with a pen in hand, noting corrections or revisions that will improve the writing. After making changes on the computer, writers should reprint the pages, adding to the pile of finished pages. Each day’s, or period’s, work should be the same: writing, rereading, editing, and making changes as one goes.

4. Identify errors and correct them. According to McCarver, three procedures are critical in the revision process: correcting mistakes, improving content, and enhancing the story.

The first attention needs to go to spelling and punctuation errors, typos, grammatical mistakes, and inconsistencies in tense or point of view. Although such mistakes may seem minor to the author, editors expect manuscripts to be virtually free of any errors.

5. Improve content. “What you say and how you say it also must be polished to the best of your ability,” states McCarver. “Improving content also includes considering the structure and sharpening your word choice,” as well as re-examining characters for consistency, making sure the plot hangs together, that scenes are compelling and dialogue natural, and that all loose ends are tied up.

Word choice is a topic for another editorial, but it is a vital part of good writing.

6. Concentrate on enhancement. Enhancement goes beyond making corrections and improving content and style: It means increasing the quality and impact of the writing. A techniques given by McCarver are as follows:

* Inserting foreshadowing for greater event impact later.

* Increasing the emotion in dialogue and thoughts in scenes.

* Adding or strengthening subplots.

* Intensifying the consequences of actions and events.

* Adding twists to the plot.

* Shortening flashbacks, if used, and including action in them.

* Making characters seem more real, depicting their actions, dialogue and thoughts more naturally and powerfully.

7. Do that final revision. After finishing the whole manuscript, revise again.

8. Take one last look. After revising the complete manuscript again, the author should reread the printed pages before mailing them or sending a query letter. All errors and last minute changes should be made.

All authors want to impress editors by providing a story that the editors cannot put down. Each author, through a manuscript, has only one chance to make a great first impression.

Note: “How to revise your FICTION” by Sam McCarver in The Writer, August, 2005, provided research material for this editorial as did several composition text books and notes from my files.

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

Review: Where Did Panther Go? by Vivian Zabel

Join along with Katie and Panther as that curious black kitty gets into all sorts of mischief.

Sunday, October 3, 2021

Building a Writing Career Takes Practice and Focus

Several years ago, my grandson, 10 at the time, was trying out for the All County Band in his area. He told me the piece he had to play was difficult. I told him that practice is a powerful tool. Just 10-15 minutes a day will help tremendously.

Obviously, the more practice the better, but my grandson, like so many kids today, has ADHD. Reducing the amount of time on practicing doesn’t make it seem overwhelming – it’s doable.

This philosophy will work for anything, including writing.

What does it take to have a flourishing writing career?

1. Learn the craft and practice it.

To be a ‘good’ writer, an effective writer, a working writer, you need to know your craft. The only way to do this is to study it.

If you’re starting out, take some courses online or offline or both. You should also read a lot of books on the craft of writing. Get a strong grasp of the basics.

We’re all familiar with “practice makes perfect.”

There’s a reason that saying has lasted. It’s true.

Writing coach Suzanne Lieurance says, “Writing is a lot like gardening because it takes constant pruning and weeding.”

You need to keep up with your craft. Even as your get better at it, keep honing your craft. Keep learning more and more and practice, practice, practice

So, what does it mean to practice?

Simple. Write. Write. Write.

An excellent way to improve your writing skills is to copy (type and/or handwrite) content of a master in the niche you want to specialize in.

This is a copywriting trick. You actually write the master’s words and how to write professionally mentally sinks in.

Now, we all know that this is just a practice tool. We should never ever use someone else’s content as our own.

A second way to improve your writing skills is to read, read, and read some more. Read books in the genre you want to write in particular. Study the books.

2. Focus in on a niche.

Have you heard the adage: A jack of all trades and master of none?

This is the reason you need to specialize.

You don’t want to be known as simply okay or good in a number of different niches. You want to be known as an expert in one or two niches.

This way, when someone is looking for a writer who specializes in, say, memoirs and autobiographies, you’re at the top of the list.

I would recommend that your niches are related, like memoirs and autobiographies or being an author and book marketing.

Along with this, focus produces results.

According to an article in Psychology Today on focus and results, Dan Goleman Ph.D. says, “The more focused we are, the more successful we can be at whatever we do. And, conversely, the more distracted, the less well we do. This applies across the board: sports, school, career.”

So, practice and focus your way to a successful writing career.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karen Cioffi is an award-winning children’s author, successful children’s ghostwriter, and online platform instructor with WOW! Women on Writing. Check out her middle-grade book, Walking Through Walls, and her new picture book series, The Adventures of Planetman.

You can connect with Karen at:

LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/karencioffiventrice

Twitter https://twitter.com/KarenCV

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/writingforchildrenwithkarencioffi/

Sunday, September 5, 2021

Writing a Story or Storytelling?

A children’s publisher (4RV’s Vivian Zabel) commented on the difference between storytelling and writing. She explained that storytelling involves visual aids, whereas writing does not.

Granted, children’s picture books do provide illustrations in the form of

visual aids, they're not the same as storytelling’s visual aids.

I had never thought of this before, but once it was said I could see it clearly.

Storytelling

Storytelling allows for the use of visual aids, which includes facial expressions. There is also voice tone, word pronunciation, along with word or phrase stressing that help aid in conveying sadness, anger, fear, and an array of other emotional sediments. This is also known as voice inflection.

Along with facial expressions and voice inflection, the storyteller can also take advantage of movement.

Imagine telling a group of children a spooky story that has the protagonist tiptoeing around a corner to see what’s there. As a storyteller you can actually tiptoe, hunched over; and exaggerating the movement enhances the suspense. Visual aids are easy to use and are powerhouses of expressions.

Another example might be if you are telling a pirate story to a young boy. You can use toy props, such as a toy sword or pirate’s hat, while limping with a pretend wooden leg. These visuals enhance the story experience for the child without the storyteller having to create the imagery with words.

Writing a Story

Writing on the other hand depends solely on the writer’s interpretation of what the facial expressions, voice, mannerisms, image, and body movement of the characters might be. And, that interpretation must be conveyed through words that preferably ‘show’ rather than ‘tell.’

If you think about it, storytelling is much easier than writing a story. But, most of us authors are writers, not storytellers, and as writers we need to convey emotions and activity through showing.

In the storytelling examples above, how might you write the scene as an author?

For the first scenario of a spooky story, one example might be:

Lucas grabbed his little brother’s hand and pulled him close. “Shhh. Don’t make any noise. It might hear us.” They crept along the wall, barely breathing, until they reached the . . .

While this passage doesn’t have the advantage of the storyteller’s visual aids, it does convey a feeling of suspense and fear.

In regard to a pirate story, as an author you might write:

Captain Sebastian grabbed his sword and heaved it above his head. “Take the ship, men.”

The pirates seized the ropes and swung onto the ship. Swords and knives clanking, they overtook their enemy.

This short passage clearly conveys a pirate scene with Captain Sebastian leading his men into a battle aboard another ship. No visual aids, but it does get its message across.

You might also note that while trying to write your story through showing, you need to watch for weak verbs, adjectives, and a host of other no-nos. In the sentence above, the words, “barely breathing” might need to be changed if it reached a publisher’s hands. Why? Because “ly” and “ing” words are also frowned upon.

So, knowing the difference, if you had your choice, which would you prefer to be, a storyteller or a writer?

I'd be a writer!

Sunday, August 1, 2021

5 Basic Functions of Dialogue

Contributed by Karen Cioffi

In an article over at Writer’s Digest, the author explained that ‘real’ dialogue doesn’t spell everything out.

So, what does this mean?

Well, people communicate with more than just words and often there’s a lot left unsaid in a conversation. Narration or the protagonist’s thoughts can fill in the blanks.

Here’s an example from “Crispin – The Cross of Lead” (honored with the John Newberry Medal for the Most Distinguished Contribution To American Literature For Children):

“Where’s Bear?” she asked when we entered the back room.

“Asleep.”

“You mustn’t be seen,” she said. “He should have told you.”

I made no reply, assuming Bear had told her of the attack on me, and that she felt a need to protect me. If Bear trusted her, I told myself, so should I.

Perfect blend of dialogue and narration.

With this in mind, let’s go over some of the functions of dialogue with the help of narration.

1. Dialogue helps reveals the character’s traits.

“Hey, Pete. Looks like you’re having some trouble with that tire. Need a hand?”

“Ugh,” moaned Pete as he struggled to lift the tire. “I-I got it.”

So, here with a bit of dialogue, it shows that Pete may have a chip on his shoulder, maybe because he’s smaller than the other character. He’d rather struggle than accept help.

Here’s another example:

“The car’s stuck in the mud. There’s no way we’re getting it out of there. It won’t budge,” said Desmond.

Brain shoved his baseball cap back on his head. “All we have to do is get the truck. We’ll hook on a tow line and pull her out.”

In this scene, through dialogue we learn that Desmond sees the cup half full – he can’t see how something can be accomplished. Brian on the other hand sees the cup half full. He knows he can get the job done. And, we know Brian wears a baseball cap.

Here’s another example:

“I’ll have turkey on rye with the mayo, lettuce, and tomato on the side. And, I’d like the bread lightly toasted. Please be sure it’s just lightly toasted. And, I’d like water, no ice, with two lemon slices on the side.”

Just from a simple lunch order, we know that the character is extremely picky. She knows what she wants and expects to get it.

I got this scenario from “When Harry Meet Sally” with Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal. It’s an amazing scene in the movie.

2. Dialogue can show what a character does for a living.

Christine looked over the documents. “Who’s responsible for these prints? They’re all wrong. The bathroom should be on the second floor and the living area should be an open concept. Somebody’s head is going to roll.”

In this scene, Christine obviously deals with blueprints. Maybe she’s an architect reviewing a subordinate’s plans. We also know she’s in charge and doesn’t take mistakes lightly.

Here’s a simple example:

“Give her oxygen and get her into the OR stat.”

From this little bit of dialogue, we can assume the person talking is a doctor and she’s working in an emergency room.

Here’s another example:

Rachel tapped the pencil on the desk. She looked around the room. Everyone was busy writing. “Man, I should have studied,” she whispered.

In this scenario we can assume Rachel is a student and her class is taking a test. We also know she wasn’t prepared for the test.

3. Dialogue can show relationships.

“Mom said you have to clean the garage before going to practice,” said Frank with a smile.

“Geez. How come you don’t have to clean the darn garage?”

From this conversation, we know the two involved are siblings, probably brothers. And, it would seem the one who has to clean the garage is older and has more chores. He’s also annoyed about that fact.

Now on the flip side, you can have information dump in dialogue – this isn’t a good thing:

“Mom said you have to clean the garage before going to practice,” said Frank with a smile.

“Geez. How come you don’t have to clean the darn garage? Just because you’re two years younger than me you get away with everything.”

It’s easy to see that the last sentence is added just to inform the reader that Frank is two years younger than his brother. This is information dump.

4. Dialogue can show how educated a character is through choice of words.

“You need to ascertain whether you and he are compatible.”

“You need to figure out if you two are a good match.”

Simple examples, but you get the point.

5. Dialogue can show tension between characters.

Sammy dropped his books and stood with his fists clenched. “Do that one more time and you’ll never do it again.”

Dylan shook his hands. “Ooohhh. I’m scared. Do you mean don’t do this again?”

This scene clearly shows tension between Sammy and Dylan. And, it shows that Dylan is the instigator of the tension.

Here’s another example:

Sara stormed up to Alicia’s desk. “You stole my idea. Mr. Peter’s is doing a full campaign based on it. Tell him it’s my idea or I’ll tell him.”

“That’s not happening,” said Alicia without hesitation. “If you weren’t careless enough to leave your notes on your desk, I wouldn’t have seen them.” She pulled a lipstick and mirror out of her desk and fixed her lips. “If you go to the boss, he won’t know who to believe. Want to risk him think you’re lying to get ahead?”

Again, this is a tension packed scene.

There are also other functions of dialogue like conveying underlying emotions, creating atmosphere, and driving the plot forward. Using dialogue and narration allows you to paint vivid pictures. Your choice of words will give your characters and your story life.

Source:

Writing a Scene with Good Dialogue and Narration

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karen Cioffi is an award-winning children’s author, successful children’s ghostwriter, and online platform instructor with WOW! Women on Writing. Check out her middle-grade book, Walking Through Walls, and her new picture book series, The Adventures of Planetman.

Monday, July 19, 2021

Building a Author Platform

A publisher requires and every author if self-publishing must have a platform and

marketing/promotion plan before a book is published. But, how does one

build a platform and what is a platform? A writer’s platform consists of

several components, but an important part is an online presence, a

presence created before publication, not after. A platform—also referred

to as an author platform or a media platform—is an established media

forum through which an author connects to his or her audience.

Here are some steps to build your author platform, but they

aren’t the only steps possible, just what I consider most important:

1. Know your target readers. If your books cover more than one genre,

then you need to target readers for all the genres. Join groups that

cater to people interested in those areas, for example, but not to

promote your books, but to promote you.

2. Identify and define your brand. What is a brand? An author brand is

an ongoing, continually evolving story that communicates what makes your

work unique, and represents an implied promise to your readers of what

they can expect you to consistently deliver.

3. Create a website – a MUST for all authors and should be up and running before your book or books are released.

4. Start blogging consistently. Blogging is one way to share your

expertise and—at the same time—build an author platform. Don’t blog just

about your writing, but find areas you know about or have researched,

maybe for a book, and blog about them. Blogging to reach other writers

doesn’t open avenues for books sales as blogging to reach your target

readers will.

5. Build an email list. Create an email sign-up form on your website.

What? You don’t have a website yet? Okay, the first step is to set up

your new site.

While you’re at it, create a sign-up form that connects to an email

management system; here are a few of our favorite email newsletter

platforms to choose from. Put it on your homepage to capture email

addresses — and take a deep breath.

Your job is to collect emails, and to send out worthwhile content. It

may take a long time to build up your email list, and to figure out

exactly what your message is, but you need to practice having a

following.

Everyone you know is a contact. The more people you know, the more

influence you have, especially if you know people in high places.

So, what if those influencers are a couple degrees of separation from

you? People are surprising in how they choose to support fledgling

authors. I’ve witnessed seriously established authors supporting new

writers just because it feels good and they remember what it’s like to

be in your position.

In addition to the list of people you’re connected to, create a list of

people who might blurb you, from realistic to pie in the sky. Who would

be your ideal reader? Who do you dream might one day recommend your

book?

6. Write guest posts.

7. Connect offline. Attend writing conferences. Speak at writing groups, schools, or libraries.

8. Use social media wisely. Pick just two social channels. That’s right:

only two. Set up a profile on each and post once a day. If once a day

doesn’t work with your schedule, then set a schedule and keep it: once a

week, three times a week, three times a month, etc.

I use Facebook and MeWe, but if you’re into other channels or

options, try them. If you’re writing something that lends itself to

images, join Pinterest or Instagram. If your work lends itself to video,

do YouTube. Experiment to find any social media channel that works for

you and your writing without spreading yourself too thin.

The key to social media is posting regularly and engaging people. You

want shares because shares lead to more follows. Rather than spreading

yourself thin across multiple platforms, focus consistently on the two

platforms that provide the most value to you and your work.

It takes forever (seriously) to build up a following on social media, so

don’t be discouraged. Celebrate a few likes a week. Manage your

expectations. Keep going.

The best way to build an author platform is simple: start.

Just like you don’t run a marathon without training for weeks or months,

you don’t start your author platform completely at once. Building your

platform takes discipline and hard work, but if it weren’t worth it, no

one would be doing it. Building an author platform is a marathon, not a

sprint.

Sunday, July 4, 2021

The Secret of Getting Ahead

Contributed by Karen Cioffi

"The secret of getting ahead is getting started." ~ Mark Twain

Probably everyone has heard one adage or another about the first step. Well, that first step certainly applies to your writing too.

A desire to write a novel or children story is something, but taking the first step to bringing that desire to fruition is impressive.

Having an idea for a story is something. Taking that first step and bring that idea through to the end of a completed manuscript is impressive.

Here are a couple of tips to get started:

Your idea must be put into writing or a computer file. From there you need to add notes as to what your story will be about. Do you know what the setting will be? Do you have a main character in mind? Will it be a novel? Will it be a children’s middle grade book or possibly a picture book? Do you know how you want the story to start and where you’d like it to end up? Do you know what the conflict will be?

Once you have your notes down, turn them into an outline. You might add character sheets at this point.

Or, if you’re a panster, just get started on the story and watch the characters unveil themselves.

Below are a few other quotes on that first step that I hope will inspire you to get your story started today:

“Without that first step, there is no journey. Without that first step, there can be no creation, no story.”

~ Karen Cioffi

“The first step towards getting somewhere is to decide that you are not going to stay where you are.”

~ Chauncey Depew

They say it is the first step that costs the effort. I do not find it so. I am sure I could write unlimited ‘first chapters’. I have indeed written many. ~ J. R. R. Tolkien

“Take the first step, and your mind will mobilize all its forces to your aid. But the first essential is that you begin. Once the battle is started, all that is within and without you will come to your assistance.

~ Robert Collier

“Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” ~ Martin Luther King, Jr.

“The first step in solving a problem is to recognize that it does exist.” ~ Zig Ziglar

“Have a bias toward action – let’s see something happen now. You can break that big plan into small steps and take the first step right away.” ~ Indira Gandhi

So, if you have a desire to write a book or have an idea for a story, get started today – take that first step and bring it to life.

Maybe you have some notes on a story or an outline – take that first step to turn your notes, outline, or even your draft into a complete manuscript.

TAKE THE FIRST STEP TODAY!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karen Cioffi is an award-winning children’s author, successful children’s ghostwriter, and online platform instructor with WOW! Women on Writing. Check out her middle-grade book, Walking Through Walls, and her new picture book series, The Adventures of Planetman.

Sunday, June 20, 2021

Review for Peabody Pond by Brian Heinz

[Following is an official OnlineBookClub.org review of "Peabody Pond" by Brian J. Heinz.]

4 out of 4 stars

Read official review by Everydayadventure15 - Review posted Jun 19th in Young Adult

NOTE: Online Book Club sent the following to the author:

“The review of your book is marked as featured. This means it is being featured on the page OnlineBookClub.org/reviews/ and as a sticky topic in the forums. It is set to be featured until August 20, 2021.”

Peabody Pond can be purchased online through the author's 4RV Publishing page or from other online stores.